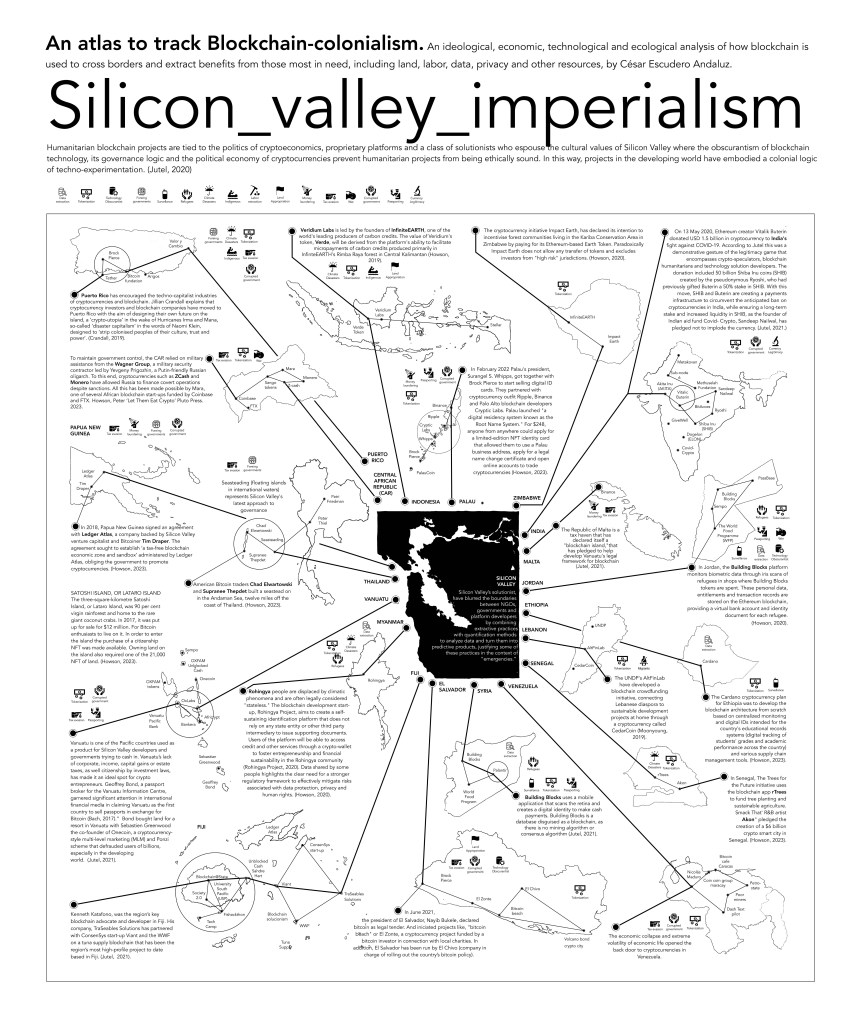

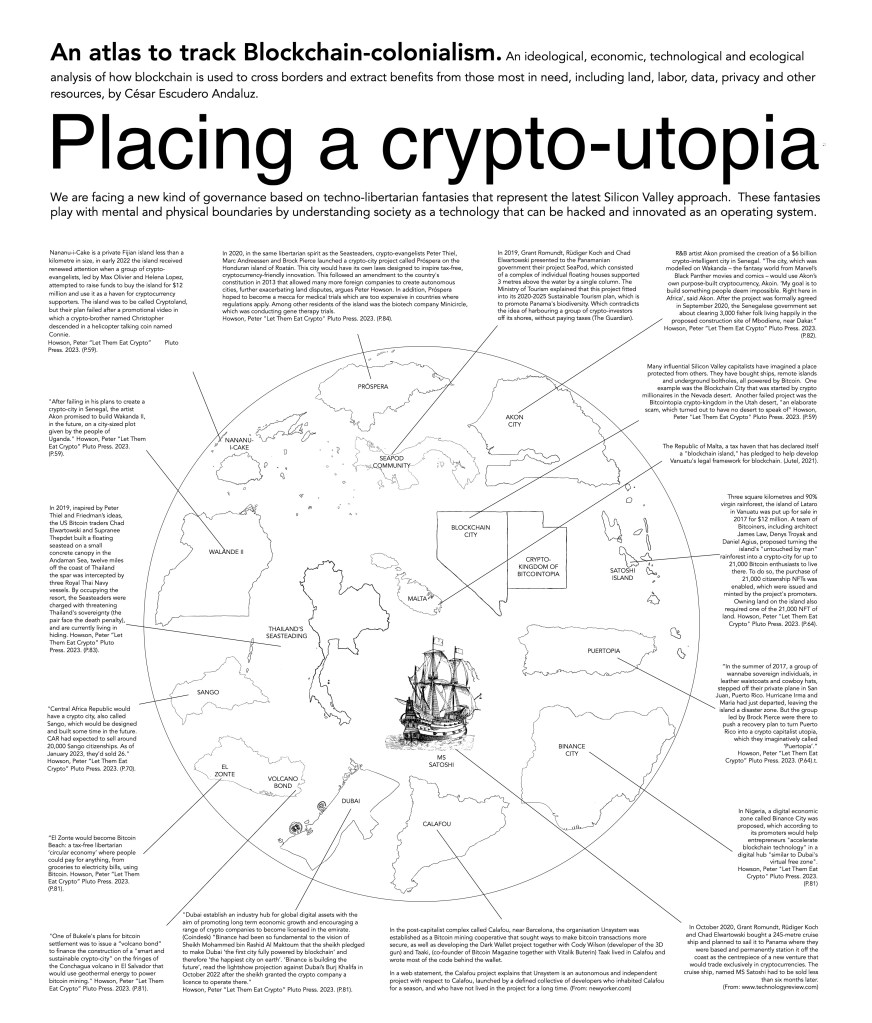

2024-ART/DIAGRAM.To understand Blockchain-Colonialism, we must go beyond cryptocurrency investments, NFTs, and metaverses to bring the user closer to a more objective reality. To create an image of it, we need to investigate the relationships between planetary resources, human labour, economics, surveillance, and privacy. In this relationship, platforms, infrastructures, devices, corporations, governments, and individuals create a complex picture that is difficult to visualize with integrity. The objective of this atlas is to monitor how individuals, corporations, and governments have used blockchain to cross borders and extract benefits from those most in need, including land, labor, data, privacy, and other resources. Authors such as Mirka Madianou, Kate Crawford, Vladan Joel, Inte Gloerich, Oliver Jutel, and Peter Howson help us to understand the colonial and extractive legacies, the promises of economic and governance alternatives imposed on fragile societies in the developing world.

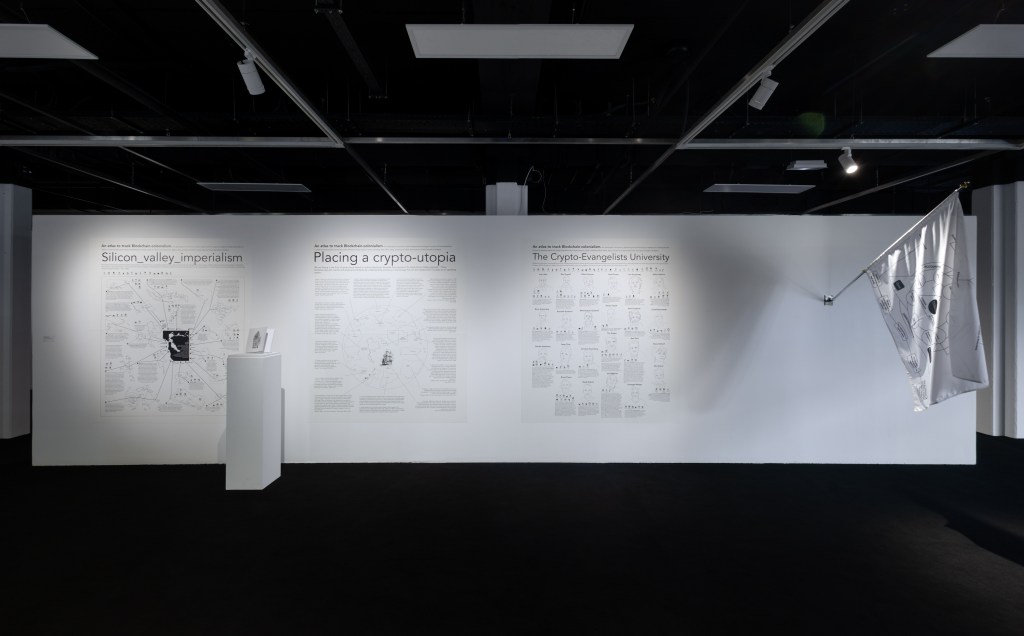

EXHIBITIONS:

2025-. “Conexiones lúcidas”, at Universitat Politècnica de València (Spain).

2024-. “The critical data research group.” WIP Festival (Cyprus).

2024-. ”ARE YOU FOR REAL” ifa, Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (Germany).

2024-. “Futuros descentralizados.” ETOPIA Center for Art and Technology (Spain).

Deconstructing blockchain rhetoric

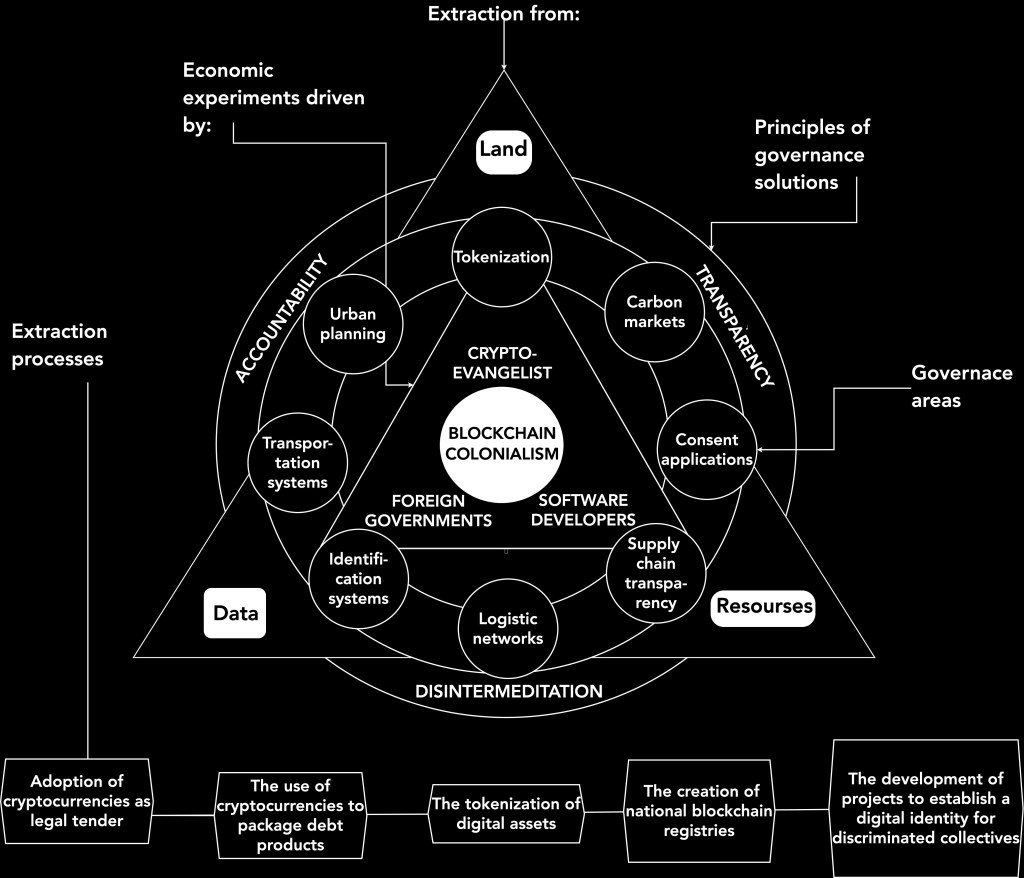

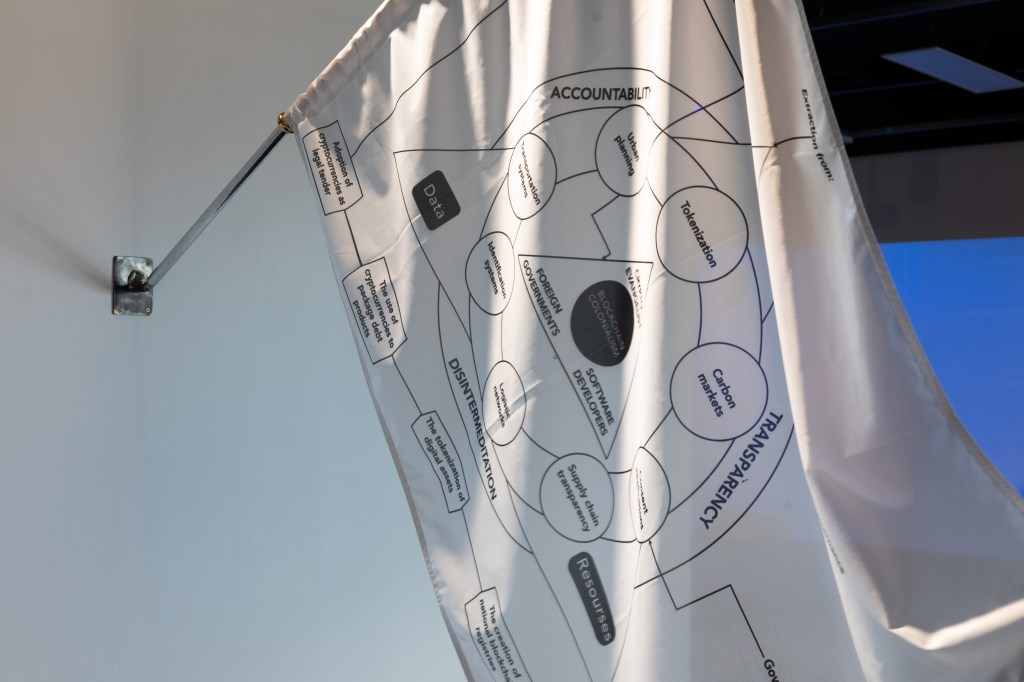

The false promise of blockchain lies in its claims of universality, which go beyond a platform that mediates data and provides services in the cloud; in the humanistic sector, blockchain aspires to influence governance systems for data production and platform dependency. In doing so, it establishes a technological frontier, where the valuable resources of the developing world become objects of paramount importance (Jutel, 2021). Moreover, blockchain behaves as a substitute for trust between people; it promises to democratise big data, offering all kinds of governance solutions under principles such as transparency, disintermediation, accountability, and efficiency. (Jutel, 2021).

Blockchain Colonialism

Blockchain colonialism encompasses economic experiments driven by foreign governments, software developers, and crypto-evangelists, who have used encryption, security, and trust emblems to extract benefits from those most in need.

This situation has been possible through different processes such as adopting cryptocurrencies as legal tender, creating national blockchain registries, using cryptocurrencies to package debt products, tokenizing digital assets, or developing projects to establish a digital identity for discriminated collectives. (Howson, 2021).

In addition, these processes have been combined with social governance systems in areas considered underdeveloped from a Western perspective, such as supply chain transparency, consent applications, logistics networks, identification and transportation systems, urban planning, and carbon market tokenization.

Silicon Valley’s solutionism

Silicon Valley’s solutionist innovation, performative entrepreneurship, and hackathons have blurred the boundaries between NGOs and platform developers that have combined extractive practices with Internet-connected computer quantification methods to analyze data and turn them into predictive products, justifying some of these practices in the context of “emergencies.” Where artificial intelligence (AI) is used, among other things, to track displaced people and predict population flows. Consequently, blockchain colonialism creates risks for non-profit organisations such as WWF, Oxfam, and UNICEF. (Howson, 2021).

Obscurantist paradigm

In addition, in vulnerable communities such as refugees, climate migrants, or local communities, blockchain projects impose and force them to give up personal data in exchange for basic needs, which can lead to unpredictable capitalization in the future. (Gloerich, 2023). According to the researcher Peter Howson, this data could also be used to make decisions about individuals, with far-reaching consequences. (Howson, 2020). For example, the US state could ration resources or determine migration rights by combining biometric data, reputational evidence, and social network data secured on the blockchain. (Jutel, 2021). Furthermore, the media professor at Goldsmiths University, Mirca Madianou, argues that states and governments increasingly use biometrics to control borders and keep out “undesirable” populations. (Madianou, 2021).

This is possible regarding technical infrastructure through mobile applications, smart contracts, and the web3 operated through engineered protocols. This means that they cannot work outside the way they are coded. Consequently, programmers and corporations have greater agency. According to Oliver Jutel, algorithmic governance and pure mediation claims make this technology obscurantist and difficult to disentangle from rhetoric and ideology. (Jutel, 2022). Another clear example is Worldcoin, a startup created by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman in 2019, which uses orbs to scan people’s eyes in exchange for a digital identity card and cryptocurrencies.

Crypto-giving

Donating and transmitting traceable digital assets through platforms such as BitGive can be more tax-efficient than selling them. Some intermediaries, such as LibraTax, offer advisory services that enable donors to transmit digital assets with the lowest possible tax burden. These services displace undue and corrupt state interference in money transfers in the relationship between donors and beneficiaries. This framing of the state as a corrupt entity in the Global South has meant that many poorer countries are not raising enough tax revenue to fund even the most basic services, such as health and education. As the UK Tax Dialogue reports, “if we are to achieve the ambitious Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), cryptocurrency platforms are ultimately an impediment to achieving those goals. (Howson, 2021).

Other fields of action used to justify crypto-colonialism are more related to transnational approaches and sustainable development, such as biodiversity conservation, climate change adaptation and mitigation, and managing carbon offsets. For example, projects like Nemus.earth and Moss.earth tokenised parts of the Amazon rainforest to sell as NFTs. These projects continue the economy of rarity established by collectible NFTs, where unique features increase land value and are governed by stakeholders in a DAO. (Gloerich, 2023). However, as in historical colonialism, these symbolic representations are abstract assets that promise future income and care little for the survival of what they represent. (Juarez, 2021).

Counter-actions

To find a more coherent way forward, Inte Gloerich argues that it is essential to create alternative spaces that challenge and resist dominant logics of exploitation to envision ways to undermine, resist, de-centre, or subvert the current situation, shedding light on the intersection of decolonial thinking, blockchain technology, and artistic practices. (Gloerich, 2023). On the other hand, Julian Crandall stresses that blockchain technology can be constructively applied through democratic participation and anti-colonial struggles and that it is essential that local developers participate in these blockchain initiatives rather than relying on outsiders. (Crandall, 2019).

Find more detailed information, diagrams and illustrations in this downloadable .PDF publication (in progress).

Images from the exhibition “Conexiones Lúcidas” Espai N-1 Biblioteca Central UPV.

REFERENCES:

[1]-. Crandall, Jillian. “Blockchains and the “Chains of Empire”: Contextualizing blockchain, cryptocurrency, and neoliberalism in . Rico.” Design and Culture 11, no. 3 (2019): 279-300.

[2]-. Dodge, Martin, and R. Kitchin. ATLASOF CYBERSPACE. London: Continuum, 2000.

[3]-. Herzfeld, Michael. “The Absent Presence: Discourses of Crypto-Colonialism.” South Atlantic Quarterly 101, no. 4 (2002): 899-926.

[4]-. Howson, Peter “Let Them Eat Crypto” Pluto Press. 2023.

[5]-. Howson, Peter. “Crypto‐giving and surveillance philanthropy: Exploring the trade‐offs in blockchain innovation for nonprofits.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 31, no. 4 (2021): 805-820.

[6]-. Howson, Peter. “Climate crises and Crypto-Colonialism: Conjuring value on the Blockchain frontiers of the global South.” Frontiers in Blockchain 3 (2020): 22.

[7]-. Inte Gloerich. Towards DAOs of Difference Reading Blockchain Through the Decolonial Thought of Sylvia Wynter,”2023. APRJA, URL: https://aprja.net//article/view/140448

[8]-. Isin E, Ruppert E Data’s empire: Postcolonial data politics. In: Bigo D, Isin E and Ruppert E (eds). Data Politics: Worlds, Subjects, Rights. London, UK: Routledge. (2019).

[9]-. Jin YD Digital Platforms, Imperialism and Political Culture. London, UK: Routledge. Crossref. (2015)

[10]-. Jutel, Olivier. “Blockchain imperialism in the Pacific.” Big Data & Society 8, no. 1 (2021): 2053951720985249.

[11]-. Juárez, Geraldine. “The Ghostchain.(or Taking Things for What They Are).” (2021).

[12]-. Lubin J (2019) 2047: A retrospective from the other side of the trust revolution. ConSenys, 27. Available at: https://media.consensys.net/highlights-from-joe-lubins-ethereal-ny-keynote-2019-7683c65d6d95 (accessed July 2019).

[13]-. Madianou, Mirca. “Technocolonialism: Digital innovation and data practices in the humanitarian response to refugee crises.” In Routledge handbook of humanitarian communication, pp. 185-202. Routledge, 2021.

[14]-. Marlinspike, Moxie, My first impressions of web3. URL: https://moxie.org/2022/01/07/web3-first-impressions.html?s=09

[15]-. O’Dwyer, Rachel and Stefan Heidenreich during the discussion “Stop Making Money: Valuation and Non-Monetary Utopias https://2018.transmediale.de/content/stop-making-money-valuation-and-non-monetary-utopias 33:00

[16]-. Rosales, Antulio, Eva van Roekel, Peter Howson, and Coco Kanters. “Poor miners and empty e-wallets: Latin American experiences with cryptocurrencies in crisis.” Human Geography (2023): 19427786231193985.

Project supported by: